The fire classification and the fire performance of external roofs are complex and often misunderstood issues, especially following the increase in legislation related to photovoltaic systems. The difficulties stem not only from the very nature of the materials and systems involved, but also from an unclear reference standard and a confusing approach to the performance statement.

Fundamental Concepts: Reaction to Fire and Fire Resistance

Before dealing specifically with the fire classification of roofs, it is necessary to clarify two key concepts: the reaction to fire of products and the fire resistance of building elements.

Reaction to fire: This is the classification of a product, once exposed to a fire source, to participate or not participate in the spread of flames. This performance derives largely (about 70%, if we want to place an educated estimate) from the material itself, but also, in part, from the type of installation and the surrounding elements (about 30%). The reaction to fire, therefore, is an intrinsic characteristic of the product, but it can be influenced by gluing, cavities or the presence of other combustible materials nearby. Under the Construction Products Regulation (CPR), this performance is usually declared in the Declaration of Performance (DOP), with a field of application that varies depending on the type of installation and interactions with other components.

Fire resistance: This classification concerns the ability of a partition element (e.g., a wall, floors and roofs, or a ceiling) to guarantee, for a given period, the stability and safety necessary to also allow the evacuation of occupants in the event of a fire. Fire Resistance classes are expressed by letters, e.g., "EI" followed by the number of minutes of resistance (e.g., EI 30, EI 60). This characteristic typically belongs to the entire separator system. It can also be declared for specific products only if they perform a separation function, such as doors or sandwich panels.

It is therefore essential to distinguish between reaction and resistance to fire:

Figure 1: Reaction to Fire of a material or product (LEFT); Fire Resistance of a separating element (RIGHT)

The first is primarily a property of the individual product, typically required for CPR

certification performance standards.The second relates to the whole system or separating element, typically associated with national fire safety regulations. Generally, CPR certification is not applicable when handling systems or product combinations, unless specified by a technical standard.

The Specificity of Roofs: A Basic Misunderstanding

In the case of external roofs, the required performance represents a mix of reaction to fire and fire resistance, thus creating significant confusion among manufacturers and other stakeholders in the sector. In particular, there remains uncertainty as to whether the performance is attributable to the individual product, e.g., the waterproofing element, or to the entire roof system, consisting of the insulation, vapour barrier and the deck.

This misconception arises from the fact that, while the CPR regulation requires that performance be declared for construction products, reality shows that fire behaviour often depends mainly on the overall system, not just the product.

The Two Components of Roof Performance

The EU fire performance of an external roof, according to EN 13501-5 and CEN/TS 1187, is

based on two main aspects:

Surface flame propagation: This aspect is closer to the concept of reaction to fire and depends about 70%* on the external covering material. The underlying substrate can also play a role, but secondary to the surface product.

Fire Penetration: This parameter closely relates to fire resistance. It evaluates whether flames can breach the separating element (the entire roof), thereby posing a risk of spreading to other compartments of the building. In this case, the external waterproofing element has little impact, while other components, such as the insulation and the deck structure, are decisive. In this case, we are in the opposite situation, with only 30%* of responsibility to be allocated to the surfacing product, with 70%* attributable to the overall roofing system.

*Note: The values of 70% and 30% are not exact figures; they are approximate numbers intended to illustrate the concept and provide a sense of scale.

This duality generates a constant debate between manufacturers and technicians, undecided on which area the performance of roofs should be declared and evaluated.

Figure 2: Surface flame propagation of a material or product (LEFT); Fire penetration through a

separating element, the roof (RIGHT)

Test Methods and Additional Complexity

The situation is further complicated by the presence of one test method, the CEN/TS 1187,

divided into four different sub-test methods for the fire classification of roofs, which evaluate different aspects. These include, in particular:

The T2 method, which focuses only on flame propagation and is more akin to reaction to fire and product certification according to CPR

The T4 method, on the other hand, mainly tests the penetration of the flame,

attributing more importance to the roof system rather than to the individual surface product, as normally done for Fire Resistance.

Therefore, it is not surprising if a roof rated Broof T2 exhibits fire penetration in practice, or if another with a Broof T4 rating shows significant surface spread during a real fire. On the contrary, this is completely normal.

In summary, with T2, 70% of the performance depends on the roof covering product, whereas with T4, the situation is reversed: only 30% is attributable to that type of product, and 70% to the system.

Note: The values 70% and 30% are not exact figures; they are approximate numbers meant to illustrate the concept and provide a sense of scale.

This confusion is also reflected in the photovoltaic sector, where the installation of panels

significantly changes the dynamics of the fire on the roof, especially regarding the surface spread of the flame.

The numbers behind the letters

After comparing the T2 and T4 methods, it's important to clarify Broof's relevance to these four approaches. The first harmonisation attempts under the Construction Products Directive failed for the roofing sector, so each country requested that its existing methods be incorporated into the new standard. This resulted in CEN/TS 1187, which has four parts, allowing each nation to use one or more methods. Countries with established procedures kept them, apart from changing the name. Thus, roofing test methods differ across countries as well as the specific composition of roofing materials, which are made to meet their chosen testing requirements. Except for T2, all methods consider two types of roof inclinations, so knowing the test's angle is key because results can also vary with the roof tilt.

Note: When mentioning the "harmonisation process" to establish a single method, it is not referring to a harmonised product standard. Instead, it is meant as a procedural approach to harmonise different EU procedures and methods.

CEN TS 1187 is not a harmonised standard; it is a horizontal technical specification used to verify external fire performance in relation to the CPR and roofing across the EU and for any products.

A "harmonised product standard" refers to a product standard that meets the requirements of the CPR, so it is something different.

Important Recommendation: Do not focus only on the term “Broof” because understanding beyond that is essential.

The table below lists the methods used by various EU and European countries.

Test method | Some Countries mainly use the method |

T1 | Spain, Portugal, Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Austria, Switzerland, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia and Hungary |

T2 | Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark and Iceland |

T3 | France and Italy |

T4 | United Kingdom, Ireland and Italy |

Let us try to understand how these methods work.

· The T1 method tests roof performance against thermal exposure from burning wooden brands (made of wood wool in a basket), without wind or other radiation sources. Roofs passing the test are rated Broof, while those failing are rated Froof. The test uses two configurations: 15° for flat roofs (up to 20°) and 45° for others. For flat roofs, flame spread is generally limited due to the lack of wind.

The test aims to verify the spread of flame and fire penetration. The test sample measures at least 800 mm x 1800 mm.

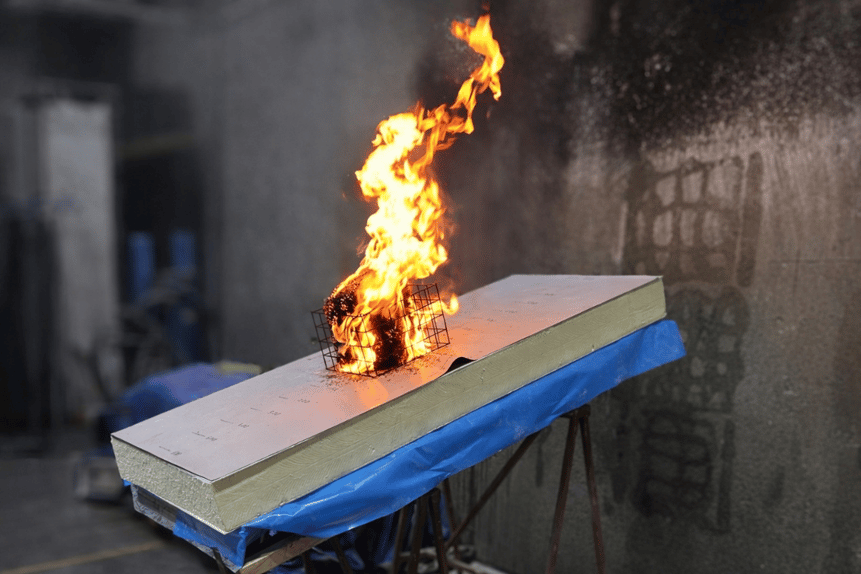

Figure 3: Example of T1 testing on a roofing system with PVC membrane, a mitigation layer

(here: AllShield BarrierSheet) and PIR insulation on a metallic deck and vapour barrier. Image courtesy of AllShield Coatings.

· The T2 method, as for T1, assigns only Broof or Froof, but based only on the surface spread of flame (as it is a test for roof coverings, not roofs) and always testing at 30°, regardless of the real application. So, a Broof T2 classification is not able to provide information about the ability to protect against fire penetration. The test is conducted without any radiation source, under two wind conditions: 2 m/s and 4 m/s, by igniting the roof covering with a wood crib.

The small size of the test sample can provide only a semi-quantitative value of the real potential extension of the flame on the roof, in case of fire. The test sample measures 1000 mm x 400 mm.

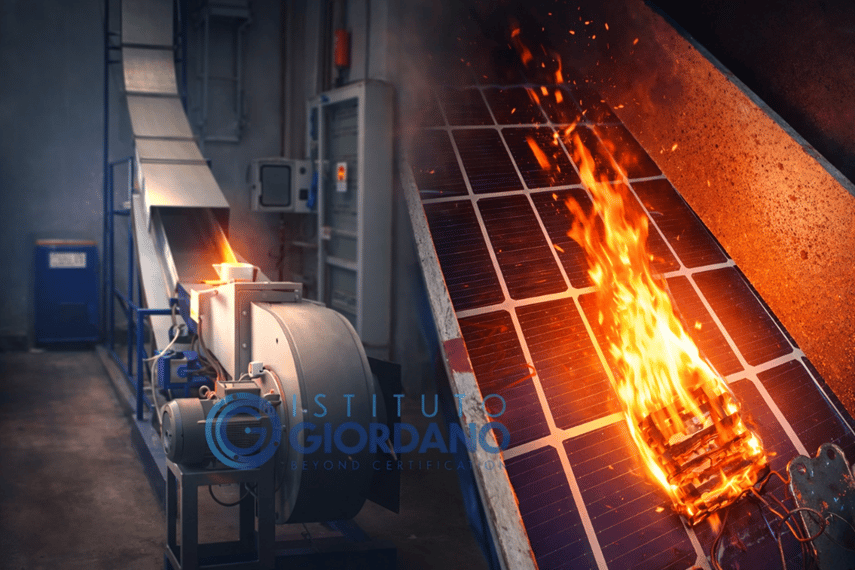

Figure 4: T2 test example on a Building Integrated Photovoltaic roof. Left: equipment setup; right: test sample at 4 m/s. Image courtesy of Istituto Giordano.

· The T3 method assigns 4 classes: Broof, Croof, Droof and Froof (as No Performance determined NPD), without the Eroof. The classification is based on the time needed by the flame to penetrate or to reach the edge of the measuring zone. This method simulates an external fire by exposing the roof to radiation and igniting it with two burning brands, while a ventilator generates a 3 m/s wind. Of the four methods, this is the most comprehensive and the test reports provide valuable data for flame propagation with respect to time.

Figure 5: T3 test example on a roofing system with Bituminous membrane and PIR insulation on a Wooden deck. Image courtesy of Istituto Giordano.

With a 3-meter test sample, it is possible to determine if a specific roofing product in a particular construction allows, for example, fire spread beyond 2 meters from the ignition zone. This information could help design protections for combustible roof openings that could channel flames indoors during, for example, a fire of PV modules above the roof. The test uses two configurations: 5° for flat roofs (up to 10°) and 30° for others (between 10° and 70°). The test sample measures 1200 mm x 3000 mm.

Figure 6: T3 test example on a roofing system with Bituminous membrane and PIR insulation on a wooden deck. The sample achieved a Broof classification, as there was no penetration, and the flame propagation (more than 2 m from the radiation zone) did not reach the edge of the measuring zone. Image courtesy of Istituto Giordano.

· The T4 method assigns 5 classes: Broof, Croof, Droof , Eroof and Froof (as No Performance determined NPD). Classification is determined by the time required for flame penetration (either 30 minutes or 60 minutes) and its progression to a designated measurement area during the preliminary test, conducted without external irradiation or wind. This methodology simulates an external fire scenario by subjecting the roof to radiation and igniting it using a specific burner for one minute, while negative pressure is generated beneath the deck through suction from the lower zone. An initial test, performed without radiation or suction and involving one minute of burner application to the roofing material, assesses the extent of flame spread. The procedure utilizes two configurations: 0° for flat roofs (with slopes up to 10°) and 45° for other roof types. Each test specimen measures 840 mm x 840 mm.

Figure 7: T4 test example on a roofing system with Bituminous membrane and PIR insulation on a Wooden deck. The sample received a Broof classification, since there was no penetration, even with a large fire on the surface. Image courtesy of Istituto Giordano.

Implications for Photovoltaics and Conclusions

A concrete example of misunderstanding can be found in some guidelines for photovoltaic systems. The addition of PV panels on the roof can promote the spread of flame, while penetration depends mainly on the composition of the roof layer by layer.

Of course, by increasing the magnitude of a fire, the fire penetration could be faster, too.

According to these guidelines, it seems appropriate to add an element with an EI 30 classification as a mitigation source to reduce the risk in case of fire.

A sheet classified EI30, useful for limiting the penetration of the flame, if covered with combustible materials poor in terms of flame propagation, can facilitate the spread of fire towards the facades of the building or towards openings that bring fire inside the building, thus affecting the real safety of the building.

Ultimately, for effective management of fire safety on external roofs, it is essential to recognise that these are two distinct phenomena, each with specific areas of action and verification methods.

Classifying performance as a whole based on consideration of only one aspect risks compromising both regulatory clarity and the real safety of buildings. Rather, it is important to clearly distinguish between two fundamentally different fire performances and ensure that both are prevented:

Surface spread

Fire penetration

At present, these are often treated as a single performance. In reality, the four alternative approaches described in TS 1187 only add to the confusion rather than resolving it.

From a regulatory clarity perspective, it remains unclear whether this performance should be declared in the membrane’s Declaration of Performance (DoP). While the industry generally regards it as a system classification, the Construction Products Regulation (CPR) does not. This results in a messy situation.

From a real-world safety perspective, addressing only one of these two aspects can lead to further complications. For example, an "EI30" rated board may improve fire penetration but does not effectively address surface spread. Therefore, it is crucial to recognise that this is a complex problem and make decisions that fit with a clear fire safety strategy for the roof and the building.

To move forward, there is a need to analyse fire performance by separating it into two parts and developing solutions for both issues, or finding one that truly works for both.

Performance Separation

To solve this situation, it would be advisable to separate the two performances: declare flame propagation as a product characteristic according to the CPR, to be declared for roof coverings and roof made of a single product, while considering the aspect related to the penetration of the flame to the roof system, outside the CPR, as is the case for Fire Resistance.

In this case, it would be easier to understand which fire performance applies to which products within the roof stratigraphy. Naturally, having a single method valid in all countries would standardise how products are introduced to the market and improve understanding of product characteristics.

This would provide a more accurate and comprehensible description of performance for both manufacturers and fire safety operators.

But this path involves complex, long, and difficult-to-implement steps.

At this stage, it is sufficient to understand the types of information that can be obtained from these four different test methods. However, it is important to note that altering the fire scenario for which they were developed may result in significantly different outcomes, as observed when a photovoltaic module is installed above them.

Obviously, it would be ideal for all stakeholders if a test could be developed that addresses both aspects simultaneously. Perhaps it could even have a classification that communicates the test performance of both spread and penetration (such as Spread B and Penetration EI30).

Note that this gets even more complex when adding a PV system on the roof.

Giombattista and Grunde

I would love to hear your thoughts! Reach out through the Burning Matters feedback form.

Eng. Giombattista Traina is the Head of the Reaction to Fire Laboratory and Research at Istituto Giordano Spa, a certification and research organization in Italy, designated as Notified Body No. 0407 under the Construction Product Regulation. He has authored numerous publications and is actively involved in standardization efforts at both national and international levels. Over the past decade, he has concentrated on developing innovative fire-testing techniques to assess the performance of photovoltaic modules and External Thermal Insulation Composite Systems (ETICS) under fire conditions.

Mr. Traina participates in several technical committees, including:

CEN/TC 127 (Fire Safety in Buildings)WG 4 (construction products), WG5 (roof) and WG7 (classification);

ISO TC 92 “Fire Safety”;

CLC TC 82 Solar Photovoltaic Energy Systems;

GNB-SH02, the horizontal sector group for Fire within GNB (Group of Notified Bodies);

CEN TC 88 WG2, Fire Subgroup on Insulations;

currently serves as the EGOLF contact person for Istituto Giordano.