Fire: A Growing Global Crisis

From building fires to wildfires, fire incidents are increasing in both frequency and intensity [1][2]. Several factors are driving this trend – urban expansion is pushing development into fire-prone areas [3], aging infrastructure is increasing the risk of ignition in cities [4], and modern materials are contributing to higher fuel load [5]. On top of that, climate change is causing longer burning times and intensifying fire behaviour [6]. Due to all these factors, no region is entirely safe, whether it is residential homes in megacities or forests in Los Angeles – fire has become a major global crisis.

Each year, fire causes massive destruction to buildings and the people inside them. More than 120,000 deaths occur annually due to fire incidents worldwide, including both residential and other structural fires [7][8]. The fatality rates are higher in developing countries, where dense population and lower fire safety standards make the impact worse [9][10]. In addition to loss of life and property, imagine if such fires reach a 500-year-old cathedral, a historical museum, a 1500-year-old Mosque, or a centuries-old library – now that would not just be property loss, it would be cultural extinction.

Devastating fire disasters around the world have pushed societies to respond scientifically, technically, and politically by raising awareness and developing proactive strategies to protect communities [11]. Yet despite this, heritage structures remain predominantly overlooked, even though they are among the most vulnerable sites [12]. For heritage structures, fire is not just a threat; it is a destroyer of history. From the 2019 Notre Dame Cathedral blaze [13] to the 2024 Børsen heritage building fire in Copenhagen [14], heritage sites are increasingly at risk, especially during renovations and in the face of climate change. Looking at past fire incidents, fire has long been erasing cultural legacies across the globe. For instance, the Palisades and Eaton fires alone led to the loss of around 35 historically significant structures [15].

As climate change fuels more intense wildfires and urban expansion, increasing exposure, the preservation of historical architecture is facing a silent emergency. Sometimes, the structure itself may not be considered as heritage, yet it holds valuable historical collections, such as museums or libraries, which carry significant cultural value. An example of this is the fire at TU Delft Faculty of Architecture on May 13, 2008. The fire started from a malfunctioning coffee machine, and it spread uncontrollably due to inadequate fire safety measures, eventually causing the collapse of a key section of the building. The loss included one of the world’s finest architectural libraries and unique furniture model collections by architects such as Rietveld and Le Corbusier – an irreplaceable loss to architectural history and knowledge [16].

Why are Heritage Buildings at Greater Risk?

Heritage buildings are cultural assets that represent the world’s history. It is essential to protect these priceless historical monuments, which attract millions of tourists from around the world to get the experience of these ancient wonders. Heritage structures around the globe are structures of distinctive architectural and cultural importance that are greatly different from each other in aspects of size, ornamentations, diversity, building fabric, design and construction process. Unfortunately, they were typically built without sufficient fire safety considerations [17]. In many cases, there were no fire safety standards at the time the buildings were designed and constructed, as the focus was primarily on beauty, royalty, strength, and religion, rather than on safety. That is why these buildings are at much higher risk today [18]. Moreover, tourists having different physical, cultural, and psychological limitations in these historic centres can cause challenges during an emergency which may be greatly exacerbated due to the complex and confusing design of heritage buildings in the event of a fire [19].

Fires in such places not only could lead to higher risk of casualties due to the tourist presence but also could threaten the loss of irreplaceable cultural treasures. Furthermore, compared to modern buildings, heritage buildings are at higher risk due to their building fabric, fire-prone materials like wood, building characteristics, outdated construction methods, ornamentation, and poor compartmentation. The danger is further increased by old electrical or gas systems, narrow surrounding streets that aid fire spread, poor design, inadequate evacuation options, resistance to renovation by older residents, and storage of flammable items. All of this highlights the urgent need for dedicated heritage fire safety planning and action [20].

The importance of heritage structures lies in the fact that they hold unique cultural and historical value, not just like any ordinary buildings, but as symbols of identity, memory, and shared history that cannot easily be replaced or rebuilt. They reflect how people of past civilizations created architectural wonders, offering insight into their way of life. Recognized and protected by UNESCO, these structures tell the story of a region’s history and serve as major attractions that generate national revenue through tourism. When fire strikes, it not only alters the architectural features and diminishes their historical worth, but it can also cause loss of life among tourists and damage a country’s international image, ultimately reducing tourism income. Past incidents have shown that many cultural heritage sites have been severely damaged or lost due to poor fire prevention and a lack of protective systems [21]. With such a fire history, fire safety for heritage buildings should be a priority.

A Long History of Heritage Fires

Fires have caused serious damage to important cultural landmarks throughout history, and they continue to do so today [22]. From ancient times to the modern era, fire has been a constant threat: the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD, the Great Fire of London in 1666, and the major fires in New York City in 1776, 1835, and 1845, as well as the Great Chicago Fire in 1871, all left lasting scars [21]. More recently, on April 15, 2019, a fire destroyed the wooden roof and spire of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris. Although the stone walls remained standing, some artworks and iconic structures are now forever gone since the fire alarm system did not alert firefighters in time [13]. On September 2, 2018, Brazil’s National Museum went up in flames, likely because of an electrical problem. The fire destroyed over 90% of its 20 million artifacts, and firefighters struggled due to low water pressure [23]. In November 1992, a fire at Windsor Castle, which was started by a spotlight hitting curtains, burned for 15 hours and destroyed parts of the State Apartments [24]. In July 1984, lightning struck York Minster, destroying its roof and part of the building, leading to a major repair effort [25].

More recently, in Copenhagen, the historic 17th-century Børsen building caught fire during renovation, damaging its famous spire and jeopardizing irreplaceable paintings and pieces of art [14]. These disasters show how vulnerable historic buildings can be. Many of these old buildings are made of old wood, do not have modern fire safety systems, and are at greater risk during renovations [21]. These events make it clear that we need better ways to plan, detect, and prevent fires in heritage sites [20].

Barriers to Heritage Fire Safety

One of the biggest challenges in heritage fire safety is that most historic buildings were never designed with fire protection in mind [17]. Constructed with flammable materials like wood, flammable fabrics, or paper-based insulation, many lack proper fire exits or compartmentalization to stop fire from spreading [26]. Additionally, outdated electrical systems make these buildings prone to electrical fires, and the risk increases during renovations, especially when hot tools are used [20][28]. Cultural heritage protection regulations limit modifications, making it difficult to add necessary passive and active fire safety measures [27]. Another major issue is poor emergency access; many heritage sites are in narrow streets or crowded areas, which slows down firefighting efforts [29]. Finally, funding and awareness are limited, especially in developing countries, where heritage fire safety is often not on a list of priorities [30].

Installing fire protection measures in heritage structures without compromising the building’s historical integrity is another significant challenge. Fire alarms or sprinklers require access inside walls and ceilings, which are often covered with historic fabrics, wallpapers, paintings, and artwork. The fear of losing historical value, concerns about water damage, installation of inside wiring, and their protected status are major reasons for the refusal of heritage fire safety measures [27]. The challenge of heritage fire safety is not just superficial; it is deep-rooted. Many heritage buildings are exempt from modern codes due to their protected status. Fire safety systems such as detectors and sprinklers may be seen as intrusive or aesthetically damaging. Meanwhile, insufficient budgets, lack of political attention, and weak coordination between fire safety engineers and heritage departments make the issue of heritage fire safety way bigger [27].

Case Study: Heritage Structures of Lahore and Istanbul

Fairly recently, the lead author of this newsletter, Jawad, visited heritage structures in two megacities – Lahore in Pakistan and Istanbul in Turkey – and the following provides various observations related to the fire safety of these historical places. With rich history, marvellous architecture, giant structures, and deep cultural values, both cities are home to some of the world’s most important heritage sites. But when it comes to fire safety, there are serious concerns in need of urgent attention. From abundant use of wood, flammable fabric, and outdated wiring to lack of fire prevention measures and narrow streets, many of these buildings are at risk if a fire ever starts [20]. The next sections provide a simple overview of observations related to fire risks, safety gaps, and areas that urgently need improvement in both Lahore and Istanbul.

Heritage Fire Safety in Lahore

Lahore is home to many important heritage buildings that reflect its rich cultural, religious, and architectural history. However, these structures face serious fire risks due to their age, traditional materials, limited modern upgrades, and lack of dedicated fire safety measures. Across these important sites, common issues include outdated or exposed wiring, heavy use of wood in construction, a lack of fire alarms and extinguishers, challenging egress paths, narrow pathways that block fire vehicle access, and little to no emergency planning or trained fire safety staff. These gaps highlight the urgent need to include proper fire risk assessments, modern safety equipment, and practical emergency plans in heritage preservation efforts [20].

The Badshahi Mosque in Lahore, built between 1671-73 under Emperor Aurangzeb, is one of the most iconic Mughal landmarks and is a UNESCO tentative world heritage site. Its grand design includes minarets, domes, and marble work that attract thousands of tourists annually [31] [32]. Though the structure makes limited use of wood and has open areas that could prevent fire spread, the wiring system is only partially renovated. Some exposed wiring remains, which could ignite a fire. There is no installed fire safety equipment such as extinguishers or alarms [20].

The Badshahi Mosque in Lahore

The Lahore Fort (Shahi Qilla) is a large historical complex accredited as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It was built and modified during different periods, most notably under Emperor Akbar in the 16th century [33]. It contains many important monuments, such as the Diwan-e-Aam, the Mughal Old Gallery, the New Gallery Museum, and the Sheesh Mahal [34]. Many of these buildings include wood in roofs, doors, beams, and lintels. Old wiring, wooden panelling, open circuit boards, and the complete absence of fire alarms and extinguishers present a high fire risk. For example, in the Sheesh Mahal, the roof support includes old wooden beams and girders, and if fire starts here, it could cause major structural damage. Emergency exits are lacking, and fire wardens are not present on-site [20].

Lahore Fort (Shahi Qilla), in Lahore

The Wazir Khan Mosque, built between 1634-39, lies deep within the walled city of Lahore [35]. Its narrow surrounding streets make it nearly impossible for fire-fighting vehicles to access it. While the structure is made of brick masonry, much of the decoration and structure involves terracotta and wood. The interior wiring is partially exposed. There are no alarms, sprinklers, or extinguishers, and wooden elements such as doors and windows increase the risk of fire spread. The renovation scaffolding is also wooden [20], which could be a topic of a standalone newsletter, especially given the recent tragic fire in Hong Kong.

The Wazir Khan Mosque

The Lahore Museum, built during the British colonial period, houses a massive collection of cultural items made from cloth, wood, paper, and other flammable materials. Though it has fire extinguishers and fire buckets filled with sand in some places, there is no automatic alarm system. Some galleries still have wooden roofs and sheet panelling, and only one main entrance and exit, which could create crowding in an emergency [20].

The Lahore Museum

The Shalamar Garden, another UNESCO World Heritage site [33], includes many wooden gates, lintels, and structural elements made from brick, soil plaster, and wood. While the open design reduces the risk of fire spread, most electric wiring is open, and circuit boards are exposed. Cameras are installed for general monitoring, but fire alarms, hydrants, and other fire safety measures are absent [20].

Shalamar Garden

Heritage Fire Safety in Istanbul

Istanbul is one of the most historically rich cities in the world, with heritage structures from both the Byzantine and Ottoman eras [36]. These buildings reflect the city's deep cultural and religious history, but many of them face fire risks due to their older infrastructure, timber construction, and lack of modern safety upgrades [37]. Although major tourist sites like Hagia Sophia have security teams and basic fire safety measures, common problems at these sites include old electrical systems, the use of flammable materials, narrow access routes, and the absence of modern fire safety systems. Many buildings appear to rely on their thick walls and open spaces to reduce fire spread, but that alone is not enough. Most locations lack emergency signage, trained fire safety teams, or clear evacuation plans. These identified fire safety shortcomings suggest that world-famous heritage sites in Istanbul would benefit significantly from stronger fire risk management and planning to prevent future disasters [38].

One of the most famous sites in Istanbul is the Hagia Sophia, which was originally built in 537 AD and has served as a church, mosque, and now a museum and mosque again [39]. Its main structure is made of stone and brick, which reduces the fire risk somehow, but inside it still contains wooden galleries, platforms, and decorative materials that are flammable. Even though there can be as many as 50,000 visitors every day, the fire safety measures appear basic. Although security teams, fire alarms and extinguishers are present in some areas, emergency plans and trained staff are not clearly visible. Some electric wiring is updated, but there are still spots with old or exposed parts.

Hagia Sophia

The Blue Mosque (Sultan Ahmed Mosque), another well-known heritage site, was built in the early 1600s and remains an active place of worship and tourist attraction [40]. Its interiors include carpets, wooden doors, and painted ceilings, all of which are at risk in case of fire. The narrow streets surrounding the mosque limit the access of fire-fighting vehicles. While there are some fire extinguishers and signs, sprinklers or fire detection systems are not apparent. Furthermore, wiring and lighting fixtures also looked outdated in certain areas.

Blue Mosque

The Topkapi Palace – built between 1460 and 1478 and once the residence of Ottoman sultans, is a huge complex with museums, storerooms, and pavilions [41]. Some of the buildings have been renovated, but many parts still have old wooden ceilings, doors, and floors. In many sections, fire safety measures are missing or outdated. Sprinkler systems are rare, and only a few portable fire extinguishers were visible. Electrical systems have been updated in some museum areas, but not consistently across the whole site. Visitor flow is large, but evacuation routes and emergency exits are not clearly marked in most buildings.

Topkapi Palace

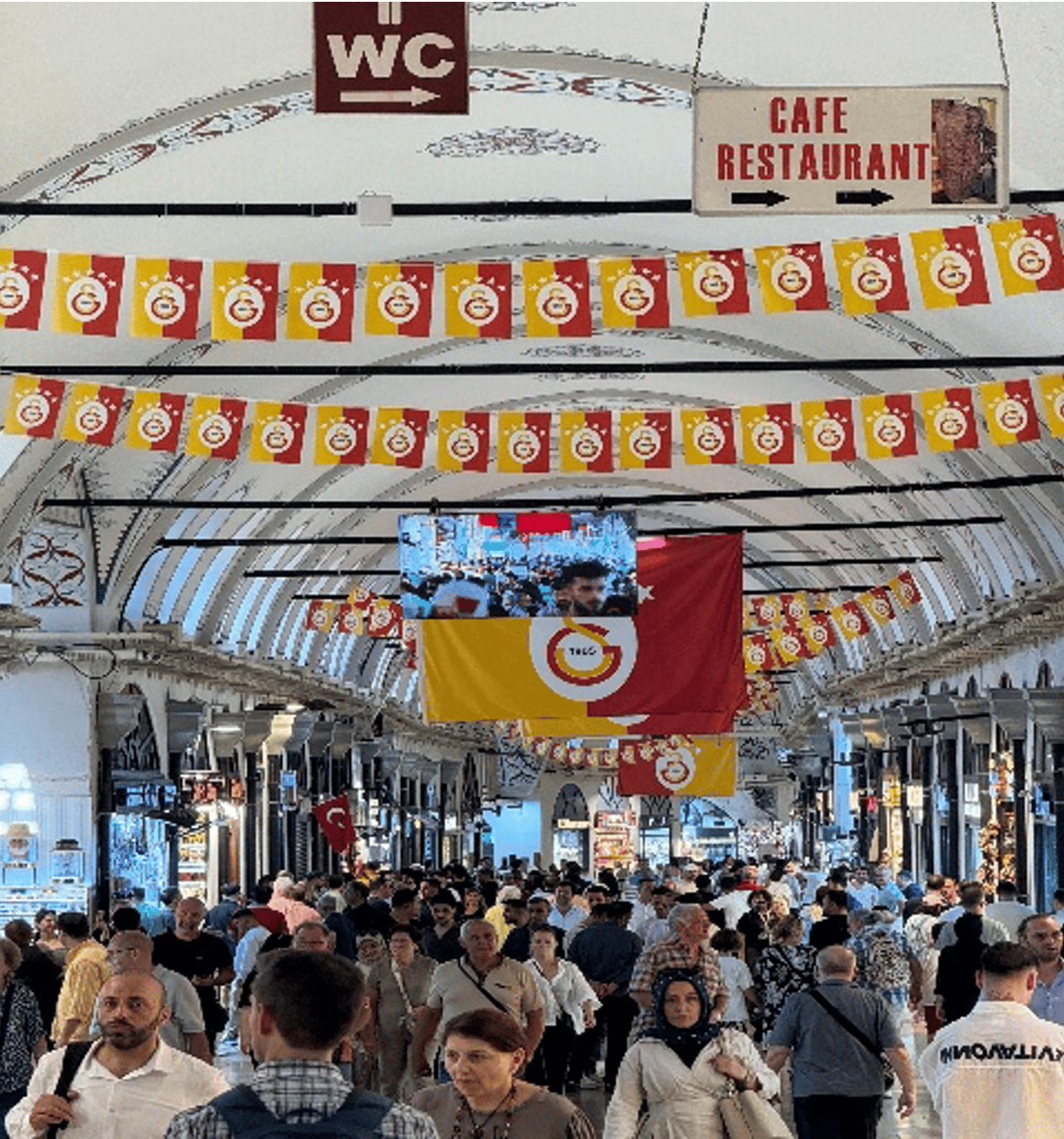

The Grand Bazaar, which was built in the 15th century, is one of the oldest and largest covered markets in the world, with thousands of shops under one roof [42]. Fire risk is especially high here because of narrow, crowded walkways, old electrical wiring, and an abundance of flammable goods like textiles and leather being sold in bulk. Firefighting access is almost impossible in the inner sections, and there is little visible fire safety equipment. If a fire breaks out, it could spread quickly and cause major loss. Some fire detection devices are installed, but many shopkeepers appear to rely on basic handheld extinguishers, which are not enough for large-scale emergencies.

Grand Bazaar

The New Mosque (Yeni Camii), built in the 17th century [43], is another Ottoman-era structure of great cultural heritage. Although it is well-preserved, it still has several fire safety shortcomings. The wooden doors, prayer rugs, and decorative panels are flammable. While the main structure is stone-based, the inside materials could catch fire easily. There were a few visible fire extinguishers, but no modern alarm system or emergency lighting was present during the visit.

New Mosque

Final Thoughts

To conclude, fire safety of heritage buildings is a pressing issue that needs immediate attention. Heritage structures around the world face significant fire safety risks due to their age, materials, complex nature, and outdated systems. As a result, they are vulnerable to both small and large-scale fires. The lack of modern fire protection systems, narrow streets, and insufficient fire safety planning all contribute to these risks. Major cultural landmarks, from the Badshahi Mosque in Lahore to the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, highlight the urgent need for fire safety measures. The past’s legacy is the future’s responsibility. With increasing tourism and the growing threat of climate change, it is important to prioritize the protection of these irreplaceable buildings to preserve our shared history for future generations. Heritage is not just about bricks, paint and elaborate ornaments; it is identity, memory, and belonging. When a historic structure burns, a part of us disappears with it.

Preserving the past is not just a conservation task – it is a fire safety mission, and the time to act is now.

Grunde

I would love to hear your thoughts! Reach out through the Burning Matters feedback form.

About the Guest Writer

Jawad Bashir Mustafvi is pursuing the International Master of Science in Fire Safety Engineering. He is currently undertaking his final semester and master’s dissertation in the programme.

As a former intern at FRISSBE, Jawad contributed to research on fire load evolution from the 1920s to the present, timber compartment fires, ETICS façade fires, building-integrated photovoltaics, and bio-based materials.

His research interests lie in fire-structure interaction, PBD for fire, fire testing, and validating fire spread simulations.

Dictate prompts and tag files automatically

Stop typing reproductions and start vibing code. Wispr Flow captures your spoken debugging flow and turns it into structured bug reports, acceptance tests, and PR descriptions. Say a file name or variable out loud and Flow preserves it exactly, tags the correct file, and keeps inline code readable. Use voice to create Cursor and Warp prompts, call out a variable like user_id, and get copy you can paste straight into an issue or PR. The result is faster triage and fewer context gaps between engineers and QA. Learn how developers use voice-first workflows in our Vibe Coding article at wisprflow.ai. Try Wispr Flow for engineers.

References

[1] A. Mandalapu, K. Seong, and J. Jiao, “Evaluating urban fire vulnerability and accessibility to fire stations and hospitals in Austin, Texas,” PLOS Clim., vol. 3, no. 7, p. e0000448, July 2024, doi: 10.1371/journal.pclm.0000448.

[2] “Wildfires and Climate Change - NASA Science.” Accessed: Aug. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://science.nasa.gov/earth/explore/wildfires-and-climate-change/

[3] H. Mahmoud, “Reimagining a pathway to reduce built-environment loss during wildfires,” Cell Rep. Sustain., vol. 1, no. 6, p. 100121, June 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.crsus.2024.100121.

[4] A. Harakan et al., “Inter-agency collaboration in building urban fire resilience in Indonesia: how do metropolitan cities address it?,” Front. Sustain. Cities, vol. 7, p. 1492869, Feb. 2025, doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1492869.

[5] I. Džolev, M. Laban, and S. Draganić, “Survey based fire load assessment and impact analysis of fire load increment on fire development in contemporary dwellings,” Saf. Sci., vol. 135, p. 105094, Mar. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.105094.

[6] J. E. Halofsky, D. L. Peterson, and B. J. Harvey, “Changing wildfire, changing forests: the effects of climate change on fire regimes and vegetation in the Pacific Northwest, USA,” Fire Ecol., vol. 16, no. 1, p. 4, Dec. 2020, doi: 10.1186/s42408-019-0062-8.

[7] N. N. Bruslinskiy, S. V. Sokolov, and O. V. Ivanova, “How many fire deaths are in the world?” Fire and Explosion Safety, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 51–62, Aug. 2019, doi: 10.18322/pvb.2019.28.04.51-62.

[8] S. Moniruzzaman, “Fire-Related Mortality from a Global Perspective,” in Residential Fire Safety. The Society of Fire Protection Engineers Series, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023, pp. 3–12. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-06325-1_1.

[9] D. Rush et al., “Fire risk reduction on the margins of an urbanizing world,” Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J., vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 747–760, Oct. 2020, doi: 10.1108/DPM-06-2020-0191.

[10] J. Twigg, N. Christie, J. Haworth, E. Osuteye, and A. Skarlatidou, “Improved Methods for Fire Risk Assessment in Low-Income and Informal Settlements,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 139, Feb. 2017, doi: 10.3390/ijerph14020139.

[11] “Maintenance – Is it Always ‘Pay me now, or pay me later?’” Accessed: Aug. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ifmacap.org/blog/id/

[12] H. Mekonnen, Z. Bires, and K. Berhanu, “Practices and challenges of cultural heritage conservation in historical and religious heritage sites: evidence from North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia,” Herit. Sci., vol. 10, no. 1, p. 172, Oct. 2022, doi: 10.1186/s40494-022-00802-6.

[13] “Notre-Dame Cathedral Fire | Before The Fire & After the Fire.” Accessed: July 09, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.friendsofnotredamedeparis.org/notre-dame-cathedral/fire/

[14] A. Murray, “Borsen fire: Denmark endures its own Notre Dame devastation,” Apr. 21, 2024. Accessed: July 10, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-68848772

[15] C. Farmer, “‘Historic Treasures’ Lost. Los Angeles Wildfires Have Claimed Architectural Heritage Spanning Centuries.” Accessed: July 14, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mansionglobal.com/articles/historic-homes-landmarks-los-angeles-wildfires-architectural-heritage-23b8d08d

[16] Webmaster, “Is Cultural Heritage Compatible with Coffee Machines? The Delft Case Study - FIRE RISK HERITAGE.” Accessed: July 16, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.fireriskheritage.net/fire-and-cultural-heritage-losses/is-cultural-heritage-compatible-with-coffee-machines/

[17] J. L. Torero, “Fire Safety of Historical Buildings: Principles and Methodological Approach,” Int. J. Archit. Herit., vol. 13, no. 7, pp. 926–940, June 2019, doi: 10.1080/15583058.2019.1612484.

[18] N. H. Salleh, “Fire Safety in Heritage Buildings: Life vs Property Safety,” 2011, In book: Heritage Study of Muslim World (pp.61 - 72), Edition: First, Chapter: Chapter 7. doi: 10.13140/2.1.3955.5848.

[19] E. Carattin and V. Brannigan, “Controlled evacuation in historical and cultural structures: requirements, limitations and the potential for evacuation models,” presented at the 5th International Symposium on Human Behavior in Fire, London: Interscience Communication Limited, 2012, pp. 41–52.

[20] M. R. Riaz, J. B. Mustafvi, and M. S. Ishtiaq, “Fire Risk Assessment for Heritage Structures of Lahore: Current Situation and Contributing Factors,” J. Art Archit. Built Environ., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 137–163, Dec. 2023, doi: 10.32350/jaabe.62.07.

[21] E. Garcia-Castillo, I. Paya-Zaforteza, and A. Hospitaler, “Fire in heritage and historic buildings, a major challenge for the 21st century,” Dev. Built Environ., vol. 13, p. 100102, Mar. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.dibe.2022.100102.

[22] “The National Database of Fires in Heritage Buildings - Index,” HERITAGE & ECCLESIASTICAL FIRE PROTECTION - Preventing Fire, Protecting Life, Preserving Heritage. Accessed: July 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.fireprotect.me.uk/fires.html

[23] “Brazil’s national museum hit by huge fire,” Sept. 03, 2018. Accessed: July 10, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-45392668

[24] “1992: Blaze rages in Windsor Castle,” Nov. 20, 1992. Accessed: July 10, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/november/20/newsid_2551000/2551107.stm

[25] “York Minster to mark 40 years since devastating fire,” Apr. 09, 2024. Accessed: July 10, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-york-north-yorkshire-68773985

[26] Scientific department, “New UNESCO Guide: Protecting Cultural and Natural Heritage from Fire.” Accessed: July 11, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.fireriskheritage.net/publicationsand-research-documents-of-risk-to-cultural-heritage/unesco-document-on-fire-protection/

[27] C. C. Institute, “Fire Protection Issues for Historic Buildings – Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) Notes 2/6.” Accessed: July 10, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/conservation-preservation-publications/canadian-conservation-institute-notes/fire-protection-historic-buildings.html

[28] J. Jaďuďová, L. M. Osvaldová, S. Gašpercová, and D. Řehák, “The Analysis of Fire Protection for Selected Historical Buildings as a Part of Crisis Management: Slovak Case Study,” Sustainability, vol. 17, no. 15, p. 6743, July 2025, doi: 10.3390/su17156743.

[29] A. F. Furmanek, “Impact of the Fire Protection Requirements on the Cultural Heritage of the Polish Old Towns—Selected Problems,” Sustainability, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 176, Dec. 2024, doi: 10.3390/su17010176.

[30] B. A. Coutinho, “Heritage on Fire – Complexities, Potential Solutions and Current Regulations: An Exploratory Study”. M.Sc. thesis, Division of Fire Safety Engineering, Lund Univ., Lund, Sweden, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=9051087&fileOId=9051111

[31] U. M. Buksh and U. M. Malik, “A Comparative Study of Minarets of Contemporary Jamia Mosques and Mughal Historical Mosques of Lahore,” J. Art Archit. Built Environ., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 79–100, Dec. 2019, doi: 10.32350/jaabe.22.05.

[32] Badshahi Mosque – Mughal Art, The Art History Project. Accessed: Jan. 17, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://www.arthistoryproject.com/timeline/age-of-discovery/mughal-art/badshahi-mosque/

[33] U. W. H. Centre, “Fort and Shalamar Gardens in Lahore,” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed: July 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/171/

[34] R. Iftikhar, “Lahore Fort- a Mughal Monument on the Verge of Decline,” Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan. Vol. 56, no. 1, 2019.

[35] orientalarchitecture.com, “Wazir Khan Mosque, Lahore, Pakistan,” Asian Architecture. Accessed: July 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.orientalarchitecture.com/sid/573/pakistan/lahore/wazir-khan-mosque

[36] U. W. H. Centre, “Historic Areas of Istanbul,” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed: July 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/356/

[37] S. Durak, Y. Erbil, and N. Akıncıtürk, “Sustainability of an Architectural Heritage Site in Turkey: Fire Risk Assessment in Misi Village,” Int. J. Archit. Herit., vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 334–348, Apr. 2011, doi: 10.1080/15583051003642721.

[38] G. Külekçi and D. Lüleci, “Fire Risks and Occupational Safety in Historical Structures a Study on Challenges and Solutions,” Euroasia Journal of Mathematics Engineering Natural and Medical Sciences 11(37):60-76. Dec. 2024, doi: 10.5281/ZENODO.14569311.

[39] A. Diker, “Hagia Sophia: Secrets of the 1,600-year-old megastructure that has survived the collapse of empires,” CNN. Accessed: July 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.cnn.com/travel/hagia-sophia-istanbul-hidden-history

[40] “Unveiling Blue Mosque’s history in the Ottoman Empire | From construction to completion,” www.bluemosquetickets.com. Accessed: July 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.bluemosquetickets.com/history/

[41] “The Topkapı Palace Museum” Accessed: July 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/content/topkapi-palace-museum

[42] Istanbul Insider, “The Grand Bazaar of Istanbul, World’s Oldest and Biggest Covered Market,” Accessed: July 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://theistanbulinsider.com/the-grand-bazaar-of-istanbul-worlds-oldest-and-biggest-covered-market/

[43] D. Aga, “The New Mosque,” Architectuul. Accessed: July 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://architectuul.com/architecture/the-new-mosque