Growing demand for timber

In recent years, the global demand for timber-based construction has seen significant growth. This increase in demand can be attributed to a sustainability-focused society, improved properties of timber products, technological advancements in timber processing and construction techniques, and its aesthetic appeal (Ramage et al., 2017). However, as all other construction materials, the integrity and stability of timber structures must be ensured also during and after a fire. In addition, its combustibility increases the concerns over building fire safety and requires specific fire design considerations.

Incidents where the structure collapsed after extinguishment

On 18th June 2022 in Philadelphia, a firefighter was killed in a building collapse after a fire (Gernay et al., 2022). A similar incident was also reported in Switzerland in 2004 when the collapse of an underground car park killed seven members of the fire brigade, who were in the car park after successfully extinguishing the fire and cooling down the structural elements (Gernay et al., 2022). What went wrong and why did the structures collapse even after the fire, when it was cooling down?

Figure 2: Fire engulfs a timber frame residential block. Source: Timber-frame flats under spotlight as fire engulfs block, 2019.

Thermal wave propagation

One of the factors that could have contributed to this is the thermal wave propagation within the structural elements during the cooling phase of a fire, as depicted in Figure 3. In a structural element like a column, the internal temperature continues to rise as the heat continues to distribute and penetrate within the element, even when the temperature on the surface is decreasing (Gernay and Franssen, 2015). As a consequence, the capacity of the structural element to resist load further decreases as it starts to lose its mechanical properties due to the temperature increase.

Figure 3: Thermal wave propagation in a structural element. The red curve depicts the thermal gradient during the heating phase, the orange curve depicts the thermal gradient during the decay phase, and the yellow curve depicts the thermal gradient during the cooling phase.

Timber: The reduction in mechanical properties is larger than for steel/concrete

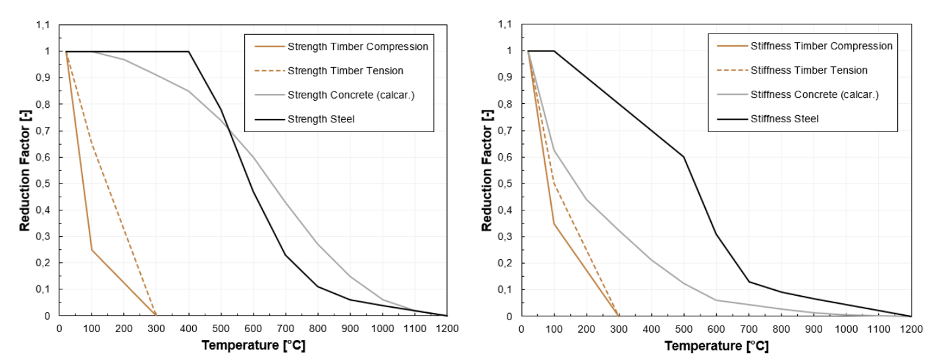

The thermal wave penetration is particularly concerning for timber structures since timber loses its mechanical properties irreversibly at temperatures as low as 65 °C (Gernay et al., 2022). Figure 4 illustrates how the mechanical properties of timber - strength (left) and stiffness (right) – decrease significantly for lower temperatures when compared to traditional construction materials like concrete and steel.

Figure 4: Comparison of the reduction factor for capacity strength (left) and stiffness (right) of steel, concrete and wood at elevated temperatures. Source: Lucherini and Colic (2024) based on (Eurocode 2 (2023), Eurocode 3 (2024), Eurocode 5 (2009).

Understanding the characteristics of timber at elevated temperatures

At elevated temperatures, around 200-280 °C, timber starts to decompose and release combustible gases (pyrolysis), and around 300 °C this process is typically completed, leaving behind charred timber (LaMalva and Hopkin, 2021). Charred timber is composed of excess carbon and is normally assumed to have negligible mechanical properties.

Therefore, when considering timber structural element (e.g., column or beam), its effective cross-section is reduced as a result of timber thermal decomposition in form of pyrolysis and charring. This leads to a reduction in the load-bearing capacity of the structural element (Lucherini et al., 2023). Hence, the charring rate (the rate at which the char layer forms) is a crucial factor for determining the load-bearing capacity of timber structures in fire.

Moreover, the thermal wave propagation during the cooling phase of fire poses a serious challenge for timber structures, particularly due to the fact that timber starts to lose its mechanical properties at relatively low temperatures.

The question that comes to the mind now is whether the current practices in fire safety design of timber buildings effectively address this issue.

Fire Safety Design for Timber Structures - Current Practices

Eurocode 5 (2009) provides guidelines for the structural fire design of timber structures. The current guidelines offer a simplified methodology called the ‘Reduced Cross-Section Method’ (RCSM), which is commonly used in fire safety engineering design. As discussed, charring is a crucial phenomenon that occurs in timber at elevated temperatures, and it is considered in the RCSM to estimate the effective load-bearing cross-section of timber structural elements. Eurocode 5 (2009) provides a method to obtain the char layer thickness by specifying the charring rate (i.e., the speed at which timber chars and penetrate within the load-bearing cross-section).

Along with the char layer thickness, a concept called ‘Zero Strength Layer’ (ZSL) is also introduced in Eurocode 5 (2009). Since timber loses its mechanical properties at relatively low temperatures, assuming that only the char layer thickness possesses null load-bearing capacity (for temperatures of 300 °C and above) may be an inadequate practice for a fire-safe design. The layers beneath the char layer are heated up and this leads to reduced mechanical properties in the heated zone. This, in turn, results in a reduced load-bearing capacity for the structural element even after the effect of the char layer is considered.

To address this concern, the concept of ZSL was recommended in Eurocode 5 (2009) for RCSM. The ZSL is meant to consider the reduction in the mechanical properties of the heated zone beneath the char layer in a timber structure. Eurocode 5 (2009) specifies a constant value of the ZSL, which is considered not to have any contribution to the load-bearing capacity (null strength).

As a result, in the Reduced Cross-Section Method, the effective char depth, considered as the timber area that does not contribute to the load-bearing capacity, is calculated by summing the char depth (estimated based on charring rate) to the ZSL. This thickness is deducted from the timber section to obtain the effective cross-sectional area. The effective cross-sectional area is assumed to have full load bearing capacity and is used to determine the capacity of the timber element during a fire. A schematic diagram of this method is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Schematic illustration of the Reduced Cross-Section Method (RCSM), which simplifies the cross-section of a timber element in char layer, zero-strength layer (ZSL) and effective cross-section

This is the general outline of how fire safety design for timber structures is performed. However, the main concern of this article was whether the current practices address the hazard of timber structures failing even after the fire is extinguished, for which the limitations of RCSM must be known. We will get to that now.

Limitations of the Reduced Cross Section Method

A review conducted by Schmid et al. (2015) reported that the method of ZSL was proposed for simply supported glue-laminated timber (GLT) beams exposed to standard fire conditions of 30 and 60 minutes on three sides. Thus, it is unknown whether the RCSM would be adequate for fire durations longer than 60 minutes or natural fires that include the fire decay and cooling phases.

A study on the thermal wave propagation in a timber element exposed to a parametric fire was conducted by Lucherini et al. (2023). The result of the study is presented in Figure 6, where the temperature evolution at various depths in the timber element is reported. It can be observed that from 70 mm depth and onwards the temperature evolution remains almost constant even after the fire temperature has decreased. From this observation, it was concluded that the thermal wave propagation continues within the timber elements even during the decay and cooling phases of fire. As a result, it was also stated that the effective char depth (char depth + ZSL) continues to increase and reaches its maximum value during or after the end of the cooling phase, thus causing the timber element to significantly reduce its capacity even after the fire is extinguished. In addition, the theoretical ZSL value obtained in the study was found to be much higher than the constant values recommended in Eurocode 5 (2009).

Hence, the current practice of fire safety design for timber structural elements appears to be inadequate, as it underestimates the ZSL and the contribution of the uncharred heated timber. As such, there is no safety-factor associated with this method.

Figure 6: Temperature evolution at various depths within the timber element, Tg is the parametric fire temperature. Source: Lucherini et al. (2023).

Conclusion

While the demand for timber-based construction is driven by its sustainability, favourable properties, and technological advancements, it is essential to address fire safety concerns adequately. Current guidelines, such as those in Eurocode 5 (2009), provide a framework for assessing the capacity of timber during and after a fire. However, studies have evidenced that the current practices may be inadequate for a safe design for timber structures under fire. Therefore, further research and revisions are needed to account for the reduction in load-bearing capacity of timber structures during fire, especially during the fire decay and cooling phase. By enhancing understanding and guidelines for fire safety in timber construction, the engineering community can ensure safe usage of timber products in the built environment.

Signed,

Akash, Andrea and Grunde

REFERENCES

EN 1992-1-2:2023. Design of concrete structures - General rules. Structural fire design.

EN 1993-1-2:2024. Design of steel structures - General rules - Structural fire design.

EN 1995-1-2:2009. Design of timber structures - General - Structural fire design

Gernay, T., Zehfuß, J., Brunkhorst, S., Robert, F., Bamonte, P., McNamee, R., Mohaine, S. and Franssen, J.-M. (2022) ‘Experimental investigation of structural failure during the cooling phase of a fire: Timber columns’. Fire and Materials, Volume 47, Issue 4, 455-460. https://doi.org/10.1002/fam.3110

Gernay, T. and Franssen, J.-M. (2015) ‘A performance indicator for structures under natural fire’, Engineering Structures, 100, pp. 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2015.06.005.

LaMalva, K. and Hopkin, D. (eds.) (2021) International Handbook of Structural Fire Engineering. Cham: Springer International Publishing (The Society of Fire Protection Engineers Series). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77123-2.

Lucherini, A. and Colic, A. (2024) ‘Timber Structures and Fire Safety: Possibilities and Limitations – Research insights.’ SFPE IMFSE Student Chapter, Belgium.

Lucherini, A., Šejnová Pitelková, D. and Mózer, V. (2023) ‘PREDICTING THE EFFECTIVE CHAR DEPTH IN TIMBER ELEMENTS EXPOSED TO NATURAL FIRES, INCLUDING THE COOLING PHASE’, in World Conference on Timber Engineering (WCTE 2023). World Conference on Timber Engineering 2023 (WCTE2023), Oslo, Norway: World Conference on Timber Engineering (WCTE 2023), pp. 1681–1690. https://doi.org/10.52202/069179-0226.

Ramage, M., Foster, R., Smith, S., Flanagan, K., & Bakker, R. (2017). Super Tall Timber: design research for the next generation of natural structure. The Journal of Architecture, 22(1), 104–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2016.1276094

Schmid, J., Just A., Klipper, M. and Fragiacomo, M., (2015) ‘The Reduced Cross-Section Method for Evaluation of the Fire Resistance of Timber Members: Discussion and Determination of the Zero-Strength Layer’, Fire Technology, 51(6), pp. 1285–1309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-014-0421-6.

Timber-frame flats under spotlight as fire engulfs block (no date) Construction Enquirer. https://www.constructionenquirer.com/2019/09/10/timber-frame-flats-under-spotlight-as-fire-engulfs-block/ (Accessed: 21 August 2024).

Relevant LinkedIn posts:

First video of the vignette (from experiments by Andreas Sæter Bøe):

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/fric-fire-research-and-innovation-centre_fric-webinar-timber-welcome-to-this-fric-activity-7237088125850664961-0ppB/

Second video of the vignette (from experiments by Thomas Gernay et al.): https://www.linkedin.com/posts/activity-6991324014673543168-Cn4_/

I would love to hear your thoughts! Reach out through the Burning Matters feedback form.