Did you know that the first net-zero building in Brussels had a fire in its BIPV installation recently?!

As urban areas strive toward sustainability, building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) and building-applied photovoltaics (BAPV) are emerging as popular technologies to help reduce reliance on traditional energy sources.

Both systems use solar energy to power buildings, but they differ significantly in design and application. BIPV, as the name suggests, integrates solar panels directly into the structure of a building, replacing traditional building materials on roofs, façades, or windows. This integration enables BIPV to fulfil both architectural and energy functions, merging energy production with aesthetic design.

BAPV, on the other hand, involves attaching solar panels to a building without integrating them into its core structural elements, making it a simpler, add-on solution for renewable energy generation.

However, in addition to many benefits, each type of design brings critical fire safety concerns that must be carefully managed. BIPV and BAPV present different fire risks due to their varied integration levels and structural impacts on the building. BIPV’s direct incorporation into building façades and roofs can create pathways for fire spread, posing unique safety challenges compared to BAPV, where solar panels have less direct interaction with the building’s primary structure. With the reported incidence of 29 fires per year per gigawatt installed for BAPV installations [1], fire safety experts question if BIPV installations may face even higher risks due to their design complexities, integrated nature, and electrical requirements.

This newsletter explores the critical differences in fire safety between BIPV and BAPV, addressing key questions that the fire safety community must consider. We examine the potential fire risks associated with BIPV installations and whether BIPV’s fire behaviour resembles façade fires more closely than rooftop fires. We explore whether installation, fire dynamics, and cavity geometry contribute to BIPV fire risks. Furthermore, we will look at the current state of fire safety research for BIPV, along with testing standards, regulatory requirements, and the technological distinctions that define each system.

What is BIPV?

In BIPV systems, PV modules are integrated into various building surfaces. They are mainly categorized into four types: BIPV-shadings (panels, louvers, blinds), BIPV-roofs (tiles, shingles, skylights), BIPV-windows (laminated glass, transparent thin films), and BIPV-facades (curtain walls, spandrel panels). Among these, solar shading receives the most research attention, presumably due to its dual purpose (reduce sun penetration and capture solar energy).

Exploring Fire Risks: Why is BIPV more onerous than BAPV?

BIPV systems present distinct fire risks compared to BAPV, largely due to their integration into a building. Unlike BAPV, which is typically mounted on rooftops with an air gap separating the modules from the building, BIPV is often installed directly onto façades, embedding PV modules as part of the building’s envelope. This setup makes BIPV more akin to façade fires, where flames can spread rapidly along the building’s vertical surface. When installed on façades, BIPV panels can act as conduits for fire, as cavities between modules and walls create a “chimney effect” that accelerates flame and smoke movement upwards, especially under windy conditions. This phenomenon is similar to the fire spread dynamics seen in cladding fires, where flames travel through narrow spaces, making them challenging to contain and extinguish. This cavity effect is less pronounced in BAPV systems, where the panels are usually mounted with a gap that allows for ventilation and reduces heat accumulation [2]. Furthermore, poor ventilation within the narrow cavities between the BIPV panels and the building wall can cause heat buildup, creating conditions that promote fire growth.

The similarity between BIPV and façade fires arises not just from the construction configuration but also from the materials involved. Façade fires can propagate rapidly, especially when combustible materials are present, posing significant risks to building occupants and structural integrity.

Arcing and hot spots meet combustible materials: a potent combination

BIPV systems are prone to ignition sources such as arcing and hot spots, which can arise from shading, installation errors, or material degradation over time. The installation process often involves complex configurations that may lead to electrical faults if not handled with precision. Note that many of these installation challenges are also largely present in BAPV systems.

For instance, incorrect installation of components such as connectors or insufficient insulation can lead to arcing—a high-temperature phenomenon where electrical currents jump across gaps. These arcs can ignite surrounding materials within seconds, with temperatures high enough to initiate combustion, particularly if certain connector brands are mismatched or poorly integrated into the overall system [3]. BIPV systems are susceptible to DC arcing within the cavities between panels and building structures. The limited accessibility to these cavities heightens this risk, making it difficult to inspect and mitigate potential faults. Arc faults, especially near polymer-based back sheets and junction boxes, are hazardous. Studies show that these components can ignite within 0.1 seconds of an arc forming, making rapid intervention crucial, but challenging, in a BIPV context. Moreover, the structural integration of BIPV means that faults can remain undetected for extended periods, especially if contaminants like dust or oxidation form on electrical contacts, increasing resistance and causing additional overheating [3].

Hot spots in photovoltaic cells can lead to localized overheating. This is a significant concern for BIPV due to the high energy content of encapsulating materials of PV cells such as EVA and PVB. EVA and PVB, rated at 40 MJ/kg and 30 MJ/kg, respectively, are combustible and can produce considerable heat when burned. If these materials are not adequately spaced, rapid fire spread can occur upon ignition due to the substantial energy release. Factors like uneven sunlight or shading, which cause some cells to heat disproportionately, exacerbate the ignition risk [3].

Replicating BIPV fires through experiments

To evaluate the fire safety performance of BIPV systems, Stølen et al. conducted a comprehensive lab test using a large-scale façade setup following the SP FIRE 105 protocol. This test simulated a realistic fire scenario with BIPV modules mounted on a timber frame wall. Observing temperature data across various points on the façade, researchers identified three key stages in fire development: an initial pre-flashover stage, a phase of intense flame exposure, and a final self-sustaining propagation phase.

Temperatures reached a critical 850 °C within the cavities, causing extensive damage in the lower rows of modules. With such high temperatures reached, it was observed that other façade materials (i.e., glass, glue, and aluminum construction) were severely compromised and caused falling debris. Vertical fire spread was also seen to occur even with the presence of combustible materials. These findings, detailed in the figure below, highlight the importance of robust fire barriers and strategic ventilation to prevent flame spread in integrated photovoltaic systems [4].

Integrating photovoltaic elements into façades requires careful attention to fire dynamics in PV systems due to the risk of faulty installations and combustible materials [5].

Data is King, yet it is lacking

Fire safety in photovoltaic (PV) systems, particularly in building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV), requires more comprehensive data collection to assess and mitigate potential risks effectively. While existing research provides a general understanding of fire risks in BAPV installations, an extensive gap exists for BIPV-specific fire data. This lack of data makes it challenging to fully gauge the fire safety profile of BIPV systems, especially as adoption rates grow. Without accurate incident records, hypothetical risks associated with BIPV remain speculative, limiting the ability of fire safety professionals to develop targeted strategies. This data gap is especially concerning given BIPV’s unique integration into buildings. BIPV differs significantly from BAPV in terms of materials and structural roles, which contribute to distinct fire risk dynamics [6]. BIPV modules often incorporate specialized materials—such as glass or composite layers—that serve as both building elements and energy generators. In contrast, BAPV systems are typically mounted externally, which simplifies fire containment and reduces direct structural risk. The materials used in BIPV, including encapsulants like EVA and PVB, as discussed above, possess calorific values that can contribute to rapid fire spread when ignited. Studies show that material and structural differences have a significant influence on the fire dynamics and fire risk profiles in BIPV and BAPV [7]. Thus, further research to establish these connections definitively is required due to the embedded nature of BIPV modules.

BIPV Standards, Testing, and Regulatory Needs

Current research maturity and standards reflect this divide between BAPV and BIPV fire safety protocols. Though system testing is still not properly established, BAPV systems have some benefit from established safety standards, such as those outlined by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). BIPV, on the other hand, though tested as a construction product, lacks comprehensive fire testing protocols specific to its unique design requirements [8], and especially as a system. As BIPV technology advances, matching these developments with updated testing and safety protocols is essential. However, existing standards often fall short of embracing BIPV’s dual roles in structural and energy functions, necessitating further study and the development of tailored protocols to address these gaps [9].

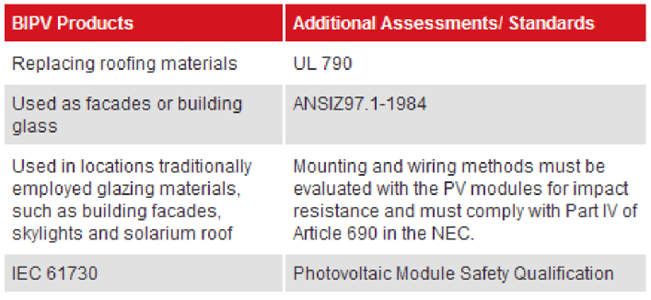

Existing standards for Building-Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV) mainly address safety and electrical aspects but often overlook the long-term performance of these systems as both solar devices and parts of building structures. As seen in the below table, there are gaps with respect to assessing BIPV as a building material and how it performs in a system. While the standards listed are robust in determining the fire performance of the PV module in isolation, distinct guidelines have yet to be developed to evaluate a BIPV system holistically.

Testing and competency requirements for BIPV installations also differ from traditional PV systems. Due to BIPV’s structural integration, advanced testing or CFD simulations are needed to accurately simulate real-world fire conditions (e.g., flame spread in ventilated cavities and ignition sources specific to BIPV designs) [10]. Additionally, making sure that installers and maintenance professionals have specialized training in BIPV is important. Studies have extensively demonstrated that improper installation or maintenance, in general PV technology, could escalate fire risks. This was seen in the work by Stølen et al.: high-energy photovoltaic components embedded directly in the building envelope can cause rapid vertical flame spread and structural disintegration of other materials in the façade system [4].

Quality control in BIPV manufacturing and updated building codes represent another critical area for improving fire safety. BIPV systems require high-quality, durable materials to withstand environmental stressors and reduce fire risks over time [11]. Furthermore, current building codes and fire safety regulations may not adequately address the fire performance requirements of BIPV modules, especially regarding flammability, smoke generation, and structural stability under fire conditions. Revising these standards to reflect BIPV’s specific fire safety challenges would enhance the resilience of buildings employing integrated PV systems and support broader adoption without compromising safety [12].

Conclusion

As the use of photovoltaic technology expands in urban architecture, especially with the growing adoption of BIPV systems, ensuring fire safety remains paramount. Current research and data reveal significant gaps in our understanding of BIPV-specific fire risks, particularly in terms of material behavior, structural integration, and the unique fire dynamics posed by embedded photovoltaic systems. Unlike BAPV, which to some extent has benefited from more established testing protocols and regulatory standards, though not on the system level, BIPV still lacks comprehensive fire data and standardized testing that account for its dual role as both a structural component and an energy generator. The absence of this data limits our ability to assess the risks fully and develop effective prevention strategies, highlighting the need for focused fire safety research dedicated to BIPV systems.

Moving forward, a collaborative approach involving fire safety experts, regulatory bodies, PV manufacturers, and building industry stakeholders is essential to bridge these gaps. Establishing robust fire safety standards and guidelines for BIPV will require input from multiple disciplines to address the unique challenges of integrating photovoltaic modules into building structures. This collaboration should focus on developing BIPV-specific fire testing protocols, updating building codes to include fire safety provisions for integrated photovoltaics, and ensuring that installers and maintenance professionals are equipped with specialized training to manage the unique risks associated with BIPV.

In closing, the urgency for prioritizing fire safety in BIPV systems cannot be overstated. As these technologies become more common in sustainable architecture, particularly in dense urban environments, the potential consequences of inadequate fire safety measures are substantial. By investing in dedicated research, fostering cross-industry collaboration, and updating regulatory frameworks, we can support the safe integration of BIPV systems, ensuring that the push toward renewable energy does not compromise building safety. Addressing these fire safety considerations today will lay the foundation for a safer, more resilient future in which solar technology can thrive without compromising the integrity of our built environment.

Call to Action

We are interested to hear your thoughts about this week’s topic on BIPV and collaborate further on BIPV-related experiments.

Join the discussion by sharing your thoughts through our Burning Matters feedback form.

References

Mohd Nizam Ong, N. A. F., Sadiq, M. A., Md Said, M. S., Jomaas, G., Mohd Tohir, M. Z., & Kristensen, J. S. (2022). Fault tree analysis of fires on rooftops with photovoltaic systems. Journal of Building Engineering, 46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103752

Ko, Y., Aram, M., Zhang, X., & Qi, D. (2022). Fire safety of building integrated photovoltaic systems: Critical review for codes and standards. Indoor and Built Environment, 31(1), 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1420326X211041739

Yang, R., Zang, Y., Yang, J., Wakefield, R., Nguyen, K., Shi, L., Trigunarsyah, B., Parolini, F., Bonomo, P., Frontini, F., Qi, D., Ko, Y., & Deng, X. (2023). Fire safety requirements for building integrated photovoltaics (BIPV): A cross-country comparison. In Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews (Vol. 173). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.113112

Stølen, K., et al. (2024). "Fire Safety of Building-Integrated Photovoltaic (BIPV) Systems: Experimental and Numerical Investigations." Fire Safety Journal, 135, 103688.

Aram, M., Zhang, X., & Qi, D. (2021). "Fire Safety of Building-Integrated Photovoltaic (BIPV) Systems: A Review." Fire Technology, 57, 1–19.

Chen, Y., et al. (2024). "Fire Safety Requirements for Building-Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV): A Cross-Country Comparison." Indoor and Built Environment, 33(1), 1–19.

Kristensen, J. S., & Jomaas, G. (2022). "Experimental Study of the Fire Behaviour on Flat Roof Constructions with Multiple Photovoltaic (PV) Panels." Fire Technology, 54, 1807–1828.

Martín-Chivelet, N., et al. (2022). "Fire Safety of Building-Integrated Photovoltaic Systems: A Review of International Standards and Regulations." Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 153, 111789.

Ding, Y., et al. (2023). "Fire Safety of Building-Integrated Photovoltaic (BIPV) Facades: A Review." Energy and Buildings, 258, 111832.

Kaplanis, S., et al. (2022). "Fire Safety Challenges of Building-Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV): A Review." Applied Energy, 306, 118054.

Yin, Y., et al. (2022). "Fire Safety of Building-Integrated Photovoltaic (BIPV) Systems: A Comprehensive Review." Journal of Building Engineering, 45, 103510.

Wang, L., et al. (2016). "Fire Safety of Building-Integrated Photovoltaic (BIPV) Systems: A Review of International Standards and Regulations." Energy Procedia, 88, 1007–1013.

Chen, L., Baghoolizadeh, M., Basem, A., Ali, S. H., Ruhani, B., Sultan, A. J., Salahshour, S., & Alizadeh, A. (2024). A comprehensive review of a building-integrated photovoltaic system (BIPV). In International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer (Vol. 159). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2024.108056